The digitization of protest. Image simultaneity, image continuity and image memory in the Ecuadorian National Strike

Miguel Alfonso Bouhaben

The digitization of protest. Image simultaneity, image continuity and image memory in the Ecuadorian National Strike

ICONO 14, Revista de comunicación y tecnologías emergentes, vol. 20, no. 2, 2022

Asociación científica ICONO 14

La digitalización de la protesta. Imagen-simultaneidad, imagen-continuidad e imagen-memoria en el Paro Nacional del Ecuador

A digitalização do protesto. Imagem-simultânea, imagem-continuidade e imagem-memória na Greve Nacional do Equador

Miguel Alfonso Bouhaben  * migalfon@ucm.es

* migalfon@ucm.es

Faculty of Fine Arts. Universidad Complutense de Madrid, España

Received: 24 november 2021

Revised: 11 march 2022

Accepted: 04 july 2022

Published: 20 september 2022

Abstract: In the context of the social struggles in the second decade of the 21st century, expressed through and triggered by new communication technologies, the National Strike in Ecuador of October 2019 is useful for exploring how social networks are used to mobilize citizen and indigenous movements. The aim of the present research is to analyse the forms of the digital production and distribution of images among three Ecuadorian collectives during the National Strike in Ecuador: Wambra, a digital community media group; Fluxus Foto, a collective of photojournalists; and First Line, an online curatorial effort. We identified three stages in this process. In the first stage, an initial corpus was determined based on the main activist strategies of creation and visual communication, which developed during the National Strike in Ecuador. In the second stage, three concepts of activist images were configured by these three active digital activist collectives during the Strike, which we explore in this analysis by alluding to their temporal praxes: image simultaneity, image continuity and image memory. Last, in the third and final stage, four categorical modalities were established allowed us to analyse each of the previous concepts of activists’ digital images: collective enunciation, plurimediality, structural openness and connectivity. These concepts have led to two fundamental conclusions: a) time provides a greater ability to choose and work with images; b) the closer an image of the present is to its production, the greater the number of visits and reactions on social media.

Keywords: digital communication; social movements; Latin American Spring; community digital media; digital photojournalism; digital curation.

Resumen: En el contexto de luchas sociales de la segunda década del siglo XXI, expresadas y desencadenadas desde las nuevas tecnologías de la comunicación, el Paro Nacional del Ecuador de octubre de 2019 supone un caso de interés para explorar los usos de las redes sociales por parte los movimientos ciudadanos e indígenas movilizados. La presente investigación tiene por objeto el análisis de las formas de producción y distribución digital de las imágenes de tres colectivos ecuatorianos durante el Paro Nacional del Ecuador: Wambra, medio comunitario digital; Fluxus Foto, colectivo de fotoperiodistas, y Primera línea, trabajo curatorial online. En la presente investigación se pueden identificar tres etapas. En la primera etapa se determinó un primer corpus con las principales estrategias activistas de creación y comunicación visual desarrolladas durante el Paro Nacional del Ecuador. En la segunda etapa se configuraron tres conceptos de imagen activista que hacen alusión a la praxis temporal y que se aplicaron al análisis de tres colectivos activistas digitales activos durante el Paro: la imagen-simultaneidad, la imagen-continuidad y la imagen-memoria. Finalmente, en la tercera y última etapa se establecieron cuatro modalidades categoriales que fueran de utilidad para analizar cada uno de los conceptos anteriores de imagen digital activista: Enunciación colectiva, Plurimedialidad, Apertura estructural y Conectividad. Estos conceptos nos han aportado dos conclusiones fundamentales: a) Hemos podido demostrar cómo el tiempo aporta una mayor capacidad para elegir y trabajar las imágenes; b) Cuanto más cerca está la imagen del presente de su producción, mayor número de visitas y reacciones.

Palabras clave: comunicación digital; movimientos sociales; Primavera Latinoamericana; medios digitales comunitarios; fotoperiodismo digital; curaduría digital.

Resumo: No contexto das lutas sociais da segunda década do século XXI, expressas e desencadeadas pelas novas tecnologias de comunicação, a Greve Nacional do Equador em outubro de 2019 é um caso de interesse para explorar os usos das redes sociais por parte do cidadão mobilizado e dos movimentos indígenas. O objetivo desta pesquisa é a análise das formas de produção e distribuição digital das imagens de três grupos equatorianos durante a Greve Nacional do Equador: Wambra, meio comunitário digital; Fluxus Foto, coletivo de fotojornalistas, e Primera Línea, curadoria online. Na presente investigação, três etapas podem ser identificadas. Na primeira etapa, foi definido um primeiro corpus com as principais estratégias ativistas de criação visual e comunicação desenvolvidas durante a Greve Nacional do Equador. Na segunda etapa, configuraram-se três conceitos de imagem ativista que aludem à práxis temporal e que foram aplicados à análise de três coletivos ativistas digitais ativos durante a greve: imagem-simultaneidade, imagem-continuidade e imagem-memória. Por fim, na terceira e última etapa, foram estabelecidas quatro modalidades categóricas úteis para analisar cada um dos conceitos anteriores de imagem digital ativista: Enunciação coletiva; Plurimedialidade, abertura estrutural e conectividade. Esses conceitos nos deram duas conclusões fundamentais: a) Pudemos demonstrar como o tempo proporciona uma maior capacidade de escolha e trabalho com imagens; b) Quanto mais próxima a imagem estiver do presente de sua produção, maior será o número de visitas e reações.

Palavras-chave: comunicação digital; movimentos sociais; Primavera latino-americana; mídia digital comunitária; fotojornalismo digital; curadoria digital.

1. Introduction

Faced with the unidirectional and totalitarian discourse of large mass media corporations, which construct events in favour of their political and economic interests, social movements have opted to configure spaces of alternative communication, which counteract the omissions and silences of the large media. In this way, social movements, from the margins, have managed to alter the univocality of the hegemonic press and radio and television media through the construction of counterdiscourses (Fraser, 1990) and countervisualities (Mierzoeff, 2016).

However, in regard to making these counterdiscourses and these countervisuals visible, social networks are essential; they enable unprecedented practices of vindication and promote greater openness, participation and horizontality in the decision-making of social movements (Carpentier, 2011; Obar et al., 2012). In addition, the social movements that act on a network build and appropriate these digital media (Pauls et al., 2022). In fact, social networks have become a fundamental tool for “internet politics” (Chadwick et al., 2006) and for solidarity and coinvolvement (Sierra, 2018), which would be incomprehensible without considering the emergence of a youth that has engaged with new technologies since its birth: so-called digital natives (Prensky, 2001). Likewise, the difficulties in scientifically evaluating “internet politics” are notable; activists are focused on their militant practices and do not show an excessive interest in social science research. In fact, some activists consider them a kind of “police science” (Hintz & Milan, 2010).

2. Referential framework. Digital and political communication. From the Arab Spring to the Latin American Spring

The Arab Spring was considered by many the first laboratory where new technologies played a transformative role. For the first time in history, protests took place in real time, both in squares and on the internet, which allowed global visibility. During the riots in Tunisia and Egypt, social networks were flooded with images and videos of the protests. However, each of these networks had a discrete strategic functionality: “Facebook was used to schedule the protests, Twitter to coordinate them and YouTube to tell the world” (Manrique, 2011). During these mobilizations, Facebook was one of the main platforms for summoning people to the streets in Egypt. Twitter informed Egyptian users that it enabled the possibility of instantly translating messages from Arabic to English to facilitate the flow of information (Morales Reyes, 2017). Thus, the success of the Arab Spring lies in the free communication of networks; for this reason, it has also been called the “wikirrevolution” (Castells, 2011) or “twitterrevolution” (Rodríguez, 2011).

Months later, the 15 M movement in Spain made use of similar digital strategies. In fact, 15 M was born from the public outrage when a video of the violent eviction of the first occupants of the Puerta del Sol in Madrid on March 15, 2011, went viral on social networks. From that moment, 15 M used networks as effective tools for coordination and self-organization and the decentralization of communication (Serrano, 2013; Monterde, 2013; Bouhaben, 2014). By May 15, 2011, the use of Facebook and Twitter had increased significantly. Facebook transcended the intentionality of its owners by being reterritorialized by the movement as a tool of resistance. For its part, the role of Twitter was defined by the use of hashtags that quickly became trending topics: the hashtag #acampadasol was mentioned 1,892,511 times, and #spanishrevolution had 1,584,871 mentions (Candón, 2013). However, in addition to this reappropriation and disruptive use of commercial networks, 15 M used other technological alternatives that had greater power to reflect the interests of social movements, such as the N-1 network, a project of “free social networks—secure, federated and self-managed” (Candón, 2013, p. 147).

In this context of social struggle in the second decade of the 21st century, expressed through and unleashed by new technologies, the National Strike in Ecuador of October 2019 is a useful case for exploring the use of social networks by citizens and indigenous peoples to mobilize social movements. In contrast to traditional media, such as the newspaper El Comercio, which focused on protest violence and said little about the deaths of protesters (Chavero, 2020) while configuring a quasi-racist image of indigenous peoples (Pérez, 2020), similar to Teleamazonas and Ecuador TV, which justified the actions of the government of Lenín Moreno, as well as its silence on and manipulation of events (Bouhaben, 2020), social networks were established as a legitimate and reliable medium for information. On these networks, the Strike was mostly supported, in contrast to the one-way discourse of the traditional media. Citizens themselves became producers of information and recorded, with their cell phones, the events that were then disseminated through social networks. However, the most important producers were community digital media, such as Wambra, which broadcast what was happening in the streets live on Facebook. Other digital media, such as GK, echoed the viralization of the Strike’s hashtags: “During the first day of the National Strike alone, on October 3, 2019, the main hashtags related to the National Strike grouped more than 150 thousand tweets. On the last day, October 13, the main hashtags related to the crisis exceeded 200 thousand tweets” (Roa, 2019).

Framed in this context, the aim of the present research aims is to analyse three Ecuadorian groups’ forms of the digital production and distribution of images of during the National Strike in Ecuador: Wambra, a digital community media group; Fluxus Foto, a group of photojournalists who publish their work on their social networks; and First Line, an online curatorial effort completed a year after the National Strike using artistic images of it. In the case of Wambra and Fluxus Foto, their publications from the beginning of the strike on October 2 to its end on October 13 were analysed. In the case of First Line, its social networks were analysed for the same timeframe one year later. In this way, based on these three cases, we address the following research questions: How is the countervisuality of social movements constructed in the National Strike in Ecuador? What are the temporal uses of the digital activist image in each of the three cases? What differences exist in the temporal praxes of the distribution of digital activist images? What concepts underlie these temporal praxes? Under what categorical modalities are these concepts of digital activist images expressed in each of the cases?

3. Methodology

Before addressing our research questions, it is necessary to expose and identify the three focal stages chronologically.

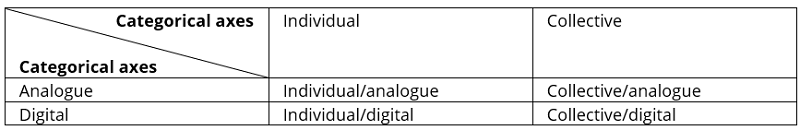

In the first stage, an initial corpus was determined by using the main activist strategies of creation and visual communication that developed during the National Strike in Ecuador. Given that the corpus of activist images was extremely extensive—reaching a total of 52 images of various aesthetic-political actors—the decision was made to take a first step. Thus, two categorical axes were established, the individual/collective axis and the analogue/digital axis, which allowed the organization and preliminary classification of the visual material. The crossing of both axes established four types of images: individual-analogue, individual-digital, collective-analogue and collective-digital. The last type is the one that was of greatest interest to us, i.e., the images made by groups in digital environments. This exploration of the corpus of activist images, based on the collective and the digital, revealed a new categorical axis: the streaming/memory axis. Among the collective-digital images we selected, some were the result of the live transmissions of the mobilizations and images in the present tense, while others were images from the past that the groups published on their social networks sometime after they were made. In this way, the actions of each activist collective revealed different temporal uses of the activist image in the context of the mobilizations of the National Strike in Ecuador (Table 1).

In the second stage, three concepts of activist images were configured to analyse the temporal praxes among the three active digital activist collectives during the strike: a) Image simultaneity, as an activist image in the present tense—a result of the live and direct recording of the actions of each social movement. This practice of streaming, common in the field of cyberjournalism, allows sharing news in real time through digital platforms. To account for this image simultaneity, we analysed the production and distribution of activist images by the digital community communication collective Wambra. b) Image continuity, as an activist image in the present continuum, serves to make visible and publicize mobilizations. To assess such image continuity, we explored the work of Fluxus Foto, a collective of documentary photographers who recorded and distributed, through their social networks, the images of the mobilizations. Unlike Wambra, Fluxus Foto published its images one day after they were recorded; thus, there was a short period of time to make a small selection of what was published. c) Image memory is the last temporal stratum of activist images; it is the image in the past that is the result of the historical trace of a social movement. To evaluate this type of image, we explored the work of First Line digital curation, an effort curated by Ana Rosa Valdez, which proposed to build a memory of the Ecuadorian National Strike through the gaze of artists, illustrators, photographers and documentary makers (Table 2).

In the third and final stage, four categorical modalities were established that were useful for analysing each of the previous concepts of activist digital images. In this stage, our interviews with Vicho Gaibor, David Diaz Arcos, Karen Toro, Andrés Yépez and Josué Alarcón of the Fluxus Foto collective, with Jorge Cano, director of the community communication collective Wambra, and with Ana Rosa Valdéz, curator of First Line, were key. Likewise, it was necessary to address the varied and profuse literature on the use of new technologies by social movements. The categorical modes were as follows: a) Collective enunciation is a categorical mode that allowed us to assess how these groups assume their activist role through collective action. Their activist images are the result of heteroglossia (Bajtin, 1929/1993) and a multiplicity of voices (Deleuze & Guattari, 1980/2004; Bifo Berardi, 2017). b) Plurimediality, as a categorical mode, alludes to the intertextual plurality that arises from the intersection of different disciplines (Duguet, 2007; Brea, 2002). c) Structural opening is a modality that alludes to the open nature of the images on a network, i.e., nonclosed images that are continuously composed, recomposed and susceptible to being traced and reread by other users of a network (Campanelli, 2011; Rovira, 2017); d) Connectivity. This allowed us to measure the interactive possibilities of the images on the networks. Navigating through images entails a nonlinear and rhizomatic act of reading (Deleuze & Guattari, 1980/2004) that makes it possible to forge freely distributed networks (Barandiaran and Aguilera, 2015).

Stage 1: Preliminary definition of the corpus with the construction of the categorical axes

Source: Own elaboration.

Stage 2: Definition of the corpus based on the three concepts of activist images that allude to temporal praxes

Source: Own elaboration.

Definition of the categorical modes for analysing the three concepts of activist images according to their temporal praxis

Source: Own elaboration.

4. Analysis and discussion of the results

4.1. Wambra and image simultaneity

Wambra is a digital community media outlet that has worked for 15 years in the field of popular and community communication in Ecuador. It is a group that is close to the indigenous and collective rights movements due to its tradition of transmitting social mobilizations. Its accumulation of such previous experiences was reflected in the October protest.

Fundamentally, Wambra was the most followed digital medium during the live coverage of the mobilizations. This live coverage, where the images of events are transmitted by social networks in real time, is what we define as image simultaneity. Image simultaneity, despite having a wide range of uses, from online conferences to video surveillance, can also have an activist use. In the case of Wambra, we have a digital medium that transmitted the protests in the present tense and allowed interactions among activists and citizens, who commented on images at the same time (Figure 1). This immediacy of an image has a certain connection with what Gilles Deleuze (1987) calls points of the present, where “there is never a succession of presents that pass, but a simultaneity of the different presents distributed by the various characters, so that each of them forms a plausible combination, possible in itself, but that all together are incomposable” (p. 139). Although both are similar in their embodiment of the simultaneous, image simultaneity points to the simultaneity between the register of the real and its distribution, while points of the present allude to the simultaneity of two fictional presents.

Figure 1

Image simultaneity: Wambra broadcasts and live comments from activists and citizens

Source: Wambra Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/WambraEC/

Specifically, image simultaneity was implemented by the Wambra community medium according to the four modes that we have defined in our methodology:

-

Collective enunciation. For Deleuze & Guattari (1980/2004), collective enunciation is a “set of concordant voices” (p. 134). In the practices of Wambra, we observe these collective mechanisms of enunciation at two levels:

-

Collective enunciation of a social movement. The National Strike in Ecuador is an example of how very diverse groups, e.g., indigenous, evangelist, student, feminist or environmentalist, tried to establish common links and agendas. Undoubtedly, this convergence of diverse groups results in heteroglossia.

-

Collective enunciation of the community environment. Similarly, Wambra is the sum of a multiplicity of voices and views. As a community medium, it encourages “the participation of social and collective organizations (human rights, students, animalists, environmentalists, indigenous peoples and nationals, Afro-descendants, feminists) who want to propose communication projects for advocacy, mainly for the advancement of rights” (Cano, 2021). This mechanism of community bonding constructs the collective enunciation of image simultaneity that is collective in its production, in its distribution and in its reception.

-

-

In the plurimediality on Wambra’s social networks, various plurimedial relationships among images, audio and text can be observed (Brea, 2002; Scolari, 2013):

-

Image-text relationship of Facebook entries. This type of image-text link is always between a short text and a single image. These texts are always an invitation to follow the protests of the National Strike live; they are always outside their image and, therefore, can establish a contextual relationship with their image: “the text adds weight to the image, gravitas with a culture, a morality, an imagination” (Barthes, 1986, p. 24);

-

Image-audio ratio in live transmission. In the recording of the mobilizations that were transmitted live, tremors and sudden movements of the camera are common; these prioritize information over aesthetics. However, these trembling images in the present tense are always contextualized by journalists, who comment on the events during a previous effort and are devoid of chance. These comments are applied to images that have three characteristics: they are transmitted in real time, adopt a hesitant movement, and are a record involving a single shot without cuts. These characteristics undoubtedly account for image simultaneity.

-

-

Structural opening. As Campanelli (2011) points out, images on the internet are open and, therefore, they are always susceptible to being remixed by other users of a network. This opening implies different practices of appropriation for images. In the case of Wambra, which produced and distributed a large number of images during the Strike, its modes of reappropriation varied:

-

Reappropriation of the image as a misdirect. Wambra discovered that someone who was supposedly broadcasting the protest live “was not at that time in the protest; it was a video of us from previous days, from an account that was broadcasting as if it were real and from that moment” (Cano, 2021).

-

Reappropriation of the image as a false identity. Wambra discovered that a year after the October strike, a medium appeared that replicated its imagery: “it was called Wampra, and it took our aesthetics and our colours. After several complaints were made, they had to change their name” (Cano, 2021);

-

Reappropriation of the image as creation. There may be cases where reappropriation is legitimate, e.g., the documentary Postscript by Juan Martín Cueva, which used images from Wambra: “The work we did with Juan Martín Cueva was, initially, an approach where he wanted the images of the coverage we created for his documentary, but we proposed to do a joint production of all our material, which he could select and curate” (Cano, 2021). The result was a documentary in the form of a collage that rereads the archival images of Wambra in their connection with personal images in a kind of essayistic reflection on the indigenous uprising of October 2019. Again, these reflect the possibilities of reappropriation, especially the first two types. First, they are linked to the political power that transmits the present of image simultaneity.

-

-

Connectivity. The internet has opened a new space for connectivity that allows the existence of “decentralized and to some extent spontaneous protests, without the prominence traditionally held by traditional formal organizations such as parties and unions” (Candón, 2013, p. 73). In the case of Wambra, its online transmissions allow connectivity “to locate a specific event to generate participation and conversation at that time; (...) people are encouraged to mobilize, either digitally or in person” (Cano, 2021). In the framework of our research, Wambra is the example that has generated the greatest connectivity due, fundamentally, to its number of followers on different networks: Facebook—102,000 followers; Instagram—19,000 followers; Twitter—8,300 followers; and YouTube—1,100 subscribers. In addition, Wambra produced and distributed the most viewed videos during the protests. Its stream on October 10 had 548,000 views; that on October 14 had 464,000; and that on October 11 had 376,000.

4.2. Fluxus Foto and image continuity

The Fluxus Foto collective defines itself on its Facebook page as “a group formed by emerging photographers who seek, in the photographic work, to approach the different realities that surround us”. Their role during the National Strike involved taking to the streets to document the demonstrations under the slogan of “informing without hiding”.

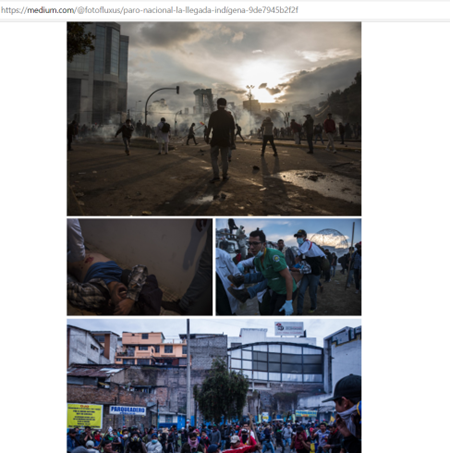

The mechanism of publication in the group consists of publishing images on social networks precisely one day after they are produced. This brief time lag between the production and distribution of an image is what define as image continuity, where a type of image in the present continuum has the purpose of documenting, the day after it is recorded, the mobilizations. This time delay is essential, as it allows the group to curate the series of images that are published on its social networks (Figure 2). In certain respects, image continuity is related to the notion of image memory proposed by Gilles Deleuze (1987) in his taxonomy of cinema. For this French philosopher, image memory is the result of the link that is established between a current image in the present and a virtual image in the past, that is, a flashback. Thus, image continuity establishes a link between an image recorded in the past and its publication in the present. On such questions regarding temporality, the group has not stopped questioning itself. Undoubtedly, image continuity has both a pragmatic side, since it serves to inform of, make visible and mobilize a specific moment, and a hermeneutic side, because over time, an image can be read in a different way: “images have a validity time per se due to the very fact of having been taken at a certain moment, and finally, they are documents that serve other people, in another time and with another reading. In this way, photos gain other values. The first value is immediacy. Being there and supporting social movements: the urgent. Then, they are transformed, and they have what is important: a historical reference” (Bouhaben, 2022, p. 246). Thus, following this reflection by Fluxus Foto itself, we can define image continuity as an image presentation that is archaeologically linked with an immediate past, providing a first layer of reading whose urgent character is the support of the mobilizations.

Figure 2

Image continuity: Selection of images from Fluxus Foto

Source: Medium. https://medium.com/@fotofluxus

As the coordinates of the concept of image continuity have been determined, if briefly, here, we explore this concept, as in the previous case study, through four modes:

-

Collective enunciation. Image continuity is formed from the interaction of two varieties of agents of enunciation collectives (Bifo Berardi, 2017):

-

Collective mode of organization. The organizational mechanics of the collective during the National Strike are based on meetings where “we all come together, we talk and each one has time to say what they think and feel about their personal work and about the collective, and then we reach an agreement” (Bouhaben, 2022, p. 243).

-

Collective mode of gaze. A member of the group may have “a very aesthetic image, but if it does not fit into the narrative that is being told at the time, it cannot be published. By collectivizing the image, individual work is already in the background” (Bouhaben, 2022, p. 245). Therefore, the collective gaze of Fluxus Foto is expressed through the perspective chosen during the work of viewing the images and their subsequent selection and publication on social networks. In this way, from various subjective views on a series of photographs, a common view is extracted. In addition, that common gaze is the fruit of an image continuity that bases selections in the present on records of the immediate past.

-

-

Plurimediality. In contrast to the previous case, here, we analyse plurimediality through two types of image-text interactions in the context of different social networks:

-

Image-text relationship in Facebook posts. As in the case of Wambra, text with a few sentences is presented along with a single image. Such text is always an invitation to share the images of the National Strike to create a critical awareness of the events.

-

Image-text relationship in Medium entries. In this case, text is longer, and a series of images is shared, which opens the possibility for deepening the descriptions of and reflections on events. Hence, we observe two ways of contextualizing, through text or image continuity.

-

-

Structural opening. The structural openness of the internet encourages the sharing of images that are often reappropriated and transformed by third parties. Remixing is a common practice in our audiovisual postmodernity—a praxis of intertextuality that is born from the recombination of images. This idea of opening is found, in the case of Fluxus Foto, in the reassembling of one of his works by the La Incre collective. This intervention is based on an image of a group of indigenous people with hidden faces. This image is doubly intervened in: first, they used Photoshop to give it the appearance of a comic image; second, it was colored pink. In this example, as the photograph itself shows, the authorship of the photograph is realized. However, the usual logic of remixing is that anyone can take an image from the internet without citing its author and then transform and resignify it before sending it to another person who, in turn, can transform and resignify it, and so on.

-

Connectivity. Regarding connectivity, we have established two types:

-

Connectivity with users. During the October strike, digital and community media had a great impact on the information ecosystem, and the number of users grew exponentially: “Before, digital media were very underestimated: All the attention and information were turned to traditional media. As a result of the strike, many people looked at what digital media were doing and began to give them greater credibility. In those days, our fanpage went from 1,000 followers to 8,000” (Bouhaben, 2022, p. 243). Currently (June 7, 2022), its number of followers is 4,313 (Facebook) and 8,184 (on Instagram).

-

Connectivity with other groups. Fluxus Foto maintains collaborations with groups from other Latin American countries via digital platforms. On Facebook, Fluxus Foto includes linksto the collectives with which it collaborates, such as Mídia Ninja in Brazil, Interference in Chile and Trasluz Photo in Mexico.

-

4.3. First Line and image memory

The objective of First Line is to revive the social struggle through the gazes of the artists, illustrators, photographers and documentary filmmakers who constructed images during the protests to build a memory of the National Strike in Ecuador in 2019. For this, Ana Rosa Valdez performed a digital curation of these images on Instagram, just one year later, in 2020. Valdez’s idea was to narrate what happened between October 2 and 13 in the previous year and thus keep alive the memory of the strike through art.

First Line demonstrates the use of a concept that links temporality and image. In this case, the final type of activist image is addressed: image memory. Image memory establishes a connective link between the past and the present and, in this sense, is similar to image continuity. However, the difference between the two lies in their time lapse: while the past-present relationship in the image continuity of Fluxus Foto has a time lapse of one day, in the case of First Line, this time period is one year. Therefore, in this case, the temporality of an image does not imply a continuity of the processes of the protests but rather the recollection of a multiplicity of images: illustrations, photographs, documentaries and posters of the mobilizations (Figure 3). On the other hand, image memory has notable similarities with the image past of Gilles Deleuze (1987), which arises from the coexistence of a multiplicity of subjective flashbacks, as in Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941). We find something similar with First Line: a multiplicity of Instagram posts with images from the National Strike that coexist in the unit of the online archive curated by Ana Rosa Valdez. The difference is that while the image past of Citizen Kane is a closed and linear image, the image memory worked into the Instagram posts of First Line configures an open structure that allows nonlinear reading: “Social networks in the reconstruction of memory? Because it offers immediate access, you can send a link or tag someone” (Valdez, 2021). However, there is always the possibility that links are broken or that technology has evolved; therefore, it is necessary to preserve these images in a physical format: “The storage memory must be in other places; we cannot leave it to the networks” (Valdez, 2021).

Figure 3

Image memory: Multiplicity of images from the digital curatorship of First Line

Source: Instagram First line. Memory of the Strike. https://www.instagram.com/memoriadelparo/

As in the previous cases, the concept of image memory is expressed through the four modes that we defined in the methodology section above:

-

Collective enunciation. The First Line project can be thought of as both heteroglossia and polyphony (Bajtin, 1929/1993), beginning with the effort of its curator, Ana Rosa Valdez, to gather visual material that was produced during the Strike and answer the following question: “What should be done with these compiled images?” To answer this question, Valdez initiated a series of contacts—first, with the photographers, illustrators and visual artists who had created the images about October and later, with CONAIE. Thus, a committee was built, a polyphony of voices and views, a heteroglossia: “It was important that everything be consensual, because the interesting thing was to see how the images worked in the contexts of social struggle. That committee included Apauti Castro, who is the communication leader of CONAIE; Andrés Tapia, CONFENIAE communication director; Manai Kowii, a Kichwa artist from Imbabura and member of the Sumakruray and Warmi Muyu collective; Jaime Núñez del Arco, a graphic designer and artist at Terminal de Ediciones; and myself, from Parallax” (Valdez). In addition to these actors, the curatorial project had the support of Marcelo Calderón de Pánico Estudio, who was in charge of the design, and Guillermo Morán, who wrote the texts that narrated the events in the Strike. In short, the participation of a multiplicity of enunciating agents in the forging that is prior to the construction of an archive is the basis on which image memory is sustained.

-

Plurimediality. First Line was nourished, in the first place, by the multiplicity of images from illustrators, photographers and documentary makers and, therefore, was a clear example of the plurimedial interweaving of different disciplines (Duguet, 2007). Instagram, which is not only a photography platform but also a multimedia communication space (Leaver et al., 2020), is a space that makes this intersection possible. On the other hand, to this multiplicity of images are added the graphic line proposed by Marcelo Calderón, which aims to represent the organized case of the mobilizations —“the idea for the graphic line was organized chaos. Behind all the sensations of chaos, there was a very strong organization of social organizations, grassroots organizations, collectives, volunteers, and marches” (Valdez, 2021)— and the texts of Guillermo Morán. In First Line, we observe how its multiplicity of images, connections between the ordered chaos of the graphic line and the texts that they contain function as a sort of intertitle that narrates the Strike. This work of multiplicity, intertextuality and plurimediality points to the images of the past that make up image memory.

-

Structural opening. The internet is a structuring construct that is indeterminate, incomplete and open, allowing users to appropriate available images (Rovira, 2017). In First Line, this openness can be explored by two different paths:

-

Opening of the compiled images. In First Line, the aesthetics of the remix are already present in the images themselves: “The artists dialogued with the aesthetics of indigenism, popular graphics or contemporary art. The objective of many of them was to remove, appropriate, cannibalize and use the artistic and visual legacies inherited from the movements and social struggles of the past” (Valdez, 2021). In the illustrations below, for example, one can observe the appropriation of indigenous symbols, such as the chacana or wiphala.

-

Opening of the incomplete online file. The aesthetics of the remix are also visible in the heterogeneous synthesis of the curatorial work. First Line is an incomplete and open online archive project: “it is not an absolute or total project; it is very fragmentary” (Valdez, 2021). Likewise, the open nature that social networks promote and that enable a nonlinear reading of the archive gives rise to the construction of image-memory.

-

-

Connectivity. For Barandiaran and Aguilera (2015), digital communication opens the possibility of forging free distributed networks. In this way, First Line takes charge of the powers provided by the use of networked images, which have a greater distribution and allow a multiplicity of connections. The hypertextual structure of its networks was used as a resource to promote free distribution: “When we made the decision to create First Line on social networks, what interested us was that in each post, there are links. Interested people could follow those links. The idea was to map certain practices and for users to refer to the websites of the artists” (Valdez, 2021). There have been other cases of hypertextual memory on social networks, such as the archive of the 15 M movement in Spain—a page where all those who participated could share their experiences and upload information, photographs, videos, etc. The idea of this memory was to facilitate the greatest possible number of narratives from 15 M. Similarly, First Line has collected the greatest number of perspectives on the Strike in a sort of hyperconnected online encyclopaedia, an “instagrammable museum” (Leaver et al., 2020). Undoubtedly, the hypertextuality of these networks favours the collective construction of knowledge and the forging of image memory.

5. Conclusions

This research is part of a series of works that strive to continue the path of philosophical methodology initiated by Gilles Deleuze (1987). This French philosopher argued that a concept is an act of philosophical creation. In his books on the philosophy of cinema, he produces a theory on the concepts that cinema arouses, which leads him to a profuse conceptual creation, innovative and disruptive, where he forges concepts such as image perception, image action, image dream, and image memory. For our part, in the works we have carried out over the last two years, we have addressed a common methodology, exploring the relationships between images and politics via the progressive creation of a series of concepts.

In this study, we have addressed the challenge of thinking about the temporal dimensions of the digital activist images produced during the National Strike in Ecuador by various groups. For this, we have created three concepts: image simultaneity, which alludes to the practice of streaming, that is, to the immediacy of the real-time productions and transmissions of the protests; image continuity, which refers to the images that were produced during the mobilizations but distributed on social networks a day later after a rapid selection process; and, finally, image memory, which refers to the relationship between the activist images produced a year prior to First Line and their subsequent reassembly.

These concepts have provided us with two fundamental conclusions:

-

We have demonstrated how time provides a greater ability to choose and work with images. Hence, image simultaneity, due to its immediacy, has a worse aesthetic value—many blurry and chaotic images can be observed—than image memory, where the time of maturation leads to a greater aesthetic level; in First Line, these images are highly elaborate, both aesthetically and technically.

-

The closer an image is to the present of its production, the greater the number of visits and reactions. That is, image simultaneity, which provides more information but is less aesthetically pleasing, has a greater social impact than image memory. For example, if we compare the most shared images of each of the case studies, we observe a large quantitative difference: the October 10 stream of the mobilizations transmitted by Wambra’s Facebook had 550,000 visits and almost 10,000 comments, while the most shared image of Fluxus Foto on Facebook was from October 11, with 1,134 reactions, 6,592 shares and 148 comments. Finally, First Line’s Instagram has 953 followers and the likes of each image range between 30 and 150.

Clearly, our aim has been to provide a new path for research on activist images that involves considering their temporal status. In this way, the present study is articulated with extant studies that value the use of technology by social movements (Chadwick, 2006; Carpentier, 2011; Obar et al., 2012; Sierra, 2018; Pauls et al., 2022) and within the framework of the possibilities opened by the cyber and video activist practices of the Arab Spring (Rodríguez, 2011; Castells, 2011; Manrique, 2011; Morales Reyes, 2017) and 15 m (Candón, 2013; Serrano, 2013); Monterde, 2013; Bouhaben, 2014).

Financing

This research is a result of the Mediaclasty and Imaging Research Project. Disruptive and subaltern visualities in videoactivism, experimental cinema and net-art within the framework of the María Zambrano Contracts for the Attraction of International Talent. Faculty of Fine Arts. Complutense University of Madrid, c/Pintor el Greco, 2. 28040 Madrid. Start date: 04/01/2022 End date: 03/31/2024. Duration: 24 months. Financing Agencies: Ministry of Universities (Spain) and by the European Union - NextGenerationEU. Total budget: 99,500.00 euros.

References

Bajtin, Mijaíl (1929/1993). La construcción de la enunciación (pp. 244-276). En Bajtin y Vigotski: la organización semiótica de la conciencia. Anthropos.

Barandiaran, Xavier, & Aguilera, Miguel (2015). Neurociencia y tecnopolítica: hacia un marco analógico para comprender la mente colectiva del 15M (pp. 163-211). En Javier Toret, Tecnopolítica y M. Editorial UOC.

Barthes, Roland (1986). Lo obvio y lo obtuso: imágenes, gestos, voces. Paidós.

Barthes, Roland (2001). S/Z, Siglo XXI.

Bifo Berardi, Franco (2017). Fenomenología del fin. Sensibilidad y mutación conectiva. Caja Negra.

Bouhaben, Miguel Alfonso (2014). La política audiovisual. Crítica y estrategia en la producción y distribución de los documentales del 15M. Fotocinema. Revista científica de cine y fotografía, 8, 223-253. https://doi.org/10.24310/Fotocinema.2014.v0i8.5952

Bouhaben, Miguel Alfonso (2020). Prácticas de videoactivismo estudiantil. El papel de los estudiantes de cine de la Universidad de las Artes en las movilizaciones del Paro Nacional de Ecuador (2019). Cinémas dAmérique Latine, 28, 19-35.

Bouhaben, Miguel Alfonso (2022). “Al colectivizar la imagen, el trabajo individual queda en un segundo plano”. Entrevista a Fluxus Foto. Ñawi: arte diseño comunicación, 6 (1), 243-249. https://nawi.espol.edu.ec/index.php/nawi/article/view/960/944

Brea, José Luis (2002). La era postmedia: acción comunicativa, prácticas (post) artísticas y dispositivos neomediales. Consorcio.

Campanelli, Vito (2011). Remix it yourself. Clueb.

Candón-Mena, José (2013). Toma la calle, toma las redes: el movimiento #15M en Internet. Atrapasueños.

Cano, Jorge (20 de mayo de 2021). Entrevista inédita de Miguel Alfonso Bouhaben

Carpentier, Nico (2011). Media and participation. A site of ideological democratic. Intellect.

Castells, Manuel (29 de enero de 2011). La wikirrevolución del jazmín. La Vanguardia. https://bit.ly/3RhtFDe

Chadwick, Mark et al. (2006). ENDF/B-VII. 0: next generation evaluated nuclear data library for nuclear science and technology. Nuclear data sheets, 107(12), 2931-3060. https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/900147

Chavero, Palmira (2020). De la disputa a la colaboración mediático-política en Ecuador. Análisis comparado de los frames mediáticos en las protestas de 2015 y 2019. Cuaderno, 112, 35-49. https://doi.org/10.18682/cdc.vi112.4090

Deleuze, Gilles & Guattari, Félix (1980/2004). Mil mesetas. Pre-textos.

Deleuze, Gilles (1987). La imagen-tiempo. Paidós.

Duguet, Anne-Marie (2007). El video se inspira en las artes plásticas (p. 289). En Alzate, A. G. & La Ferla, J. El medio es el diseño audiovisual. Universidad de Caldas.

Fraser, Nancy (1990). Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of actually existing Democracy. Social Text, 25-26, 56-80. https://doi.org/10.2307/466240

Hintz, Arne & Milan, Stefania (2010). SSRC| Social Science is Police Science: Researching Grass-Roots Activism. International Journal of Communication, 4, 8. http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/viewFile/893/458

Leaver, Tama, Highfield; Tim, & Abidin, Crystal (2020). Instagram: Visual social media cultures. Polity Press.

Manrique, Manuel (2011). Réseaux sociaux et médias d'information. Confluences Méditerranée, 4, 81-92. https://doi.org/10.3917/come.079.0081

Mierzoeff, Nicholas (2016). Cómo ver el mundo: Una nueva introducción a la cultura visual. Paidós

Monterde, Arnau (2013). Las mutaciones del movimiento red 15M (pp. 294-301). En Javier Toret, Tecnopolítica y M. Editorial UOC.

Morales Reyes, Cristian (2017). ¿Puede un Tweet o una publicación de Facebook acabar con un régimen? Las redes sociales como mecanismos de deliberación en Egipto durante la Primavera Árabe. Civilizar, 3, 3, 11-22.

Obar, Jonathan; Zube, Paul y Lampe, Clifford (2012). Advocacy 2.0: an analysis of how advocacy groups in the United States perceive and use social media as tools for facilitating civic engagement and collective action. Journal of information policy, 2, 1-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1956352

Pauls, Monica; Kelly, Benjamin; & Adorjan, Michael (2022). Researching Online Activism Using a Mixed-Methods Approach: Youth Activists on Twitter. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529603651

Pérez, Diego (2020). Representaciones en los medios impresos: movimiento indígena y paro nacional en Ecuador. Austral comunicación, 9, 2, 217-248. https://doi.org/10.26422/aucom.2020.0902.per

Prensky, Marc (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the horizon, 9(5), 1-7. http://educ116eff11.pbworks.com/f/prensky_digital%20natives.pdf

Roa, Susana (21 de octubre de 2019). La pelea por las apariencias tuiteras. GK. https://gk.city/2019/10/21/hashtags-paro-nacional-ecuador/

Rodríguez, Delia (2011). Twitterrevolución. El País Semanal. https://elpais.com/diario/2011/03/13/eps/1300001214_850215.html

Rovira, Guiomar (2017). Activismo en red y multitudes conectadas. Icaria.

Scolari, Carlos (2013) Narrativas transmedia: cuando todos los medios cuentan, Deusto.

Serrano, Eunate (2013). El 15M como medio: autoorganización y comunicación distribuida (pp. 120-133). En Javier Toret, Tecnopolítica y M. Editorial UOC.

Sierra Caballero, Francisco (2018). Ciberactivismo y movimientos sociales. El espacio público oposicional en la tecnopolítica contemporánea. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 73, 980-990. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2018-1292

Valdez, Ana Rosa (19 de mayo de 2021). Entrevista inédita de Miguel Alfonso Bouhaben.

Welles, Orson (Director). (1941). Ciudadano Kane [film]. RKO Pictures.

Author notes

* Researcher of the research project Mediaclastic and imagomachy. Disruptive and subaltern visualities in video activism, experimental cinema and net-art within the framework of the María Zambrano Contracts for the Attraction of International Talent. Faculty of Fine Arts. Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain.

Additional information

Translation to English

:

AJE (American Journal Experts)

To cite this article

:

Alfonso Bouhaben, Miguel. (2022). The digitization of protest. Image simultaneity, image continuity and image memory in the Ecuadorian National Strike. ICONO 14. Scientific Journal of Communication and Emerging Technologies, 20(2). https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v20i2.1805

ISSN: 1697-8293

Vol. 20

Num. 2

Año. 2022

The digitization of protest. Image simultaneity, image continuity and image memory in the Ecuadorian National Strike

Miguel Alfonso Bouhaben 1