The Use of Wuolah as a Collective Tool in the University Environment: Collaborative Teaching and Culture of Participation

Noelia García-Estévez, Lucia Ballesteros-Aguayo

The Use of Wuolah as a Collective Tool in the University Environment: Collaborative Teaching and Culture of Participation

ICONO 14, Revista de comunicación y tecnologías emergentes, vol. 20, no. 2, 2022

Asociación científica ICONO 14

El uso de Wuolah como herramienta de colectividad en el ámbito universitario: docencia colaborativa y cultura participativa

A utilização do Wuolah como instrumento de colectividade a nível universitário: ensino colaborativo e culture of participation

Noelia García-Estévez  * noeliagarcia@us.es

* noeliagarcia@us.es

Department of Audiovisual Communication and Advertising. Faculty of Communication. University of Seville (US), España

Lucia Ballesteros-Aguayo  ** luciaballesteros@uma.es

** luciaballesteros@uma.es

Department of Journalism. University of Málaga (UMA), España

Received: 31 march 2022

Revised: 15 may 2022

Accepted: 02 october 2022

Published: 27 october 2022

Resumen: El desarrollo de colectividades interconectadas en red presenta múltiples posibilidades en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje, al tiempo que plantea nuevos retos para el profesorado. Este artículo realiza un estudio de casos de la plataforma Wuolah con el fin de explorar el papel de las TIC y de plataformas colaborativas en el ámbito docente universitario y su capacidad para desarrollar experiencias colectivas de aprendizaje y potenciar una cultura participativa y prosumidora. Concretamente, son objetivos de esta investigación analizar la plataforma Wuolah, conocer la percepción que tienen de la misma el alumnado y el profesorado, así como estudiar la representación del estudiantado creador de contenido (prosumidor) y la del alumnado consumidor del mismo. Para ello se ha llevado a cabo una triangulación metodológica basada principalmente en seis entrevistas semiestructuradas al profesorado y al alumnado y una encuesta (n=278) al estudiantado. Los resultados obtenidos demuestran que Wuolah es la plataforma para compartir apuntes más popular entre el alumnado encuestado que valora muy positivamente su utilidad. El profesorado, en cambio, parte de un importante desconocimiento junto con ciertas reticencias con respecto a su posible contribución en la dinámica docente. Finalmente, se concluye que estas metodologías colaborativas han impactado de manera desigual entre el profesorado y el alumnado universitario, pese al interés de ambos en la necesidad de incorporar en el proceso de aprendizaje y en la práctica docente herramientas de la Web 2.0.

Palabras clave: aprendizaje; cultura participativa; docencia colaborativa; prosumidor; TIC; Wuolah.

Abstract: The development of networked collectives presents multiple possibilities in the teaching-learning process, while at the same time posing new challenges for teachers. This article carries out a case study of the Wuolah platform in order to explore the role of ICTs and collaborative platforms in the university teaching environment and their capacity to develop collective learning experiences and foster a participatory and prosumer culture. Specifically, the objectives of this research are to analyse the Wuolah platform, to find out the perception that students and teaching staff have of it, and to study the representation of the student body that creates content (prosumer) and that of the student body that consumes it. To this end, a methodological triangulation was carried out, based mainly on six semi-structured interviews with teachers and students and a survey (n=278) with students. The results obtained show that Wuolah is the most popular platform for sharing notes among the students surveyed, who value its usefulness very positively. The teaching staff, on the other hand, are not very familiar with Wuolah and have certain reticence about its possible contribution to the teaching dynamic. Finally, it is concluded that these collaborative methodologies have had an unequal impact on university teachers and students, despite the interest of both in the need to incorporate Web 2.0 tools into the learning process and teaching practice.

Keywords: learning; participatory culture; collaborative teaching; prosumer; ICT; Wuolah.

Resumo: O desenvolvimento de colectivos em rede apresenta múltiplas possibilidades no processo de ensino-aprendizagem, ao mesmo tempo que coloca novos desafios aos professores. Este artigo realiza um estudo de caso da plataforma Wuolah a fim de explorar o papel das TIC e das plataformas de colaboração no ambiente de ensino universitário e a sua capacidade para desenvolver experiências de aprendizagem colectiva e fomentar uma cultura participativa e prosumer. Especificamente, os objectivos desta investigação são analisar a plataforma Wuolah, conhecer a percepção que os estudantes e o pessoal docente têm dela, e estudar a representação do corpo estudantil que cria conteúdos (prosumer) e a do corpo estudantil que a consome. Para este fim, foi realizada uma triangulação metodológica, baseada principalmente em seis entrevistas semi-estruturadas com professores e estudantes e um inquérito (n=278) com estudantes. Os resultados obtidos mostram que o Wuolah é a plataforma mais popular para partilhar notas entre os estudantes inquiridos, que valorizam muito positivamente a sua utilidade. O pessoal docente, por outro lado, não está muito familiarizado com Wuolah e tem certas reticências no que diz respeito à sua possível contribuição para a dinâmica do ensino. Finalmente, concluímos que as metodologias de colaboração tiveram um impacto desigual em professores e alunos universitários, apesar do interesse de ambos na necessidade de incorporar ferramentas Web 2.0 no processo de aprendizagem e na prática de ensino.

Palavras-chave: aprendizagem; cultura participativa; ensino colaborativo; prosumer; TIC; Wuolah.

1. Introduction

1.1. Collectivity in the digital context

The approach to the definitions of the concepts under study is clearly essential as a starting point for any research. In the case of our analysis, collectivity refers to educational collectivities in the new digital environments. It is therefore necessary to differentiate the concept from others with which it has traditionally been associated, such as “mass,” while it is necessary to frame it within the object of our study: the emerging participatory platforms in the digital ecosystem.

Transferring the assumptions of the analogue system to the digital age implies a redefinition of the possibilities for interaction in collectivities that are no longer human-sized, physical and approachable, but planetary-sized, virtual and ungraspable (Hassan, 2020). While some have highlighted the different forms of activism and innovation presented by this new way of conceiving digital society - while also warning of the possibility of new mechanisms of digital manipulation - (Leistert, 2017), others underline the characteristics that make digital consumer culture unique: consumer empowerment, reciprocity between the online and offline worlds and the decompartmentalisation of identities (Bidit et al., 2020).

Within this equation, the public audience is an essential part. Mediated audiences are defined as global entities in the sense of their virtual and almost instantaneous access to people, texts, and images (Raymond, 2021). The digital consumer culture facilitates the emergence of different social groups based on other common reasons, such as, for example, common interests, shared habits, choice of celebrities, support for political positions, and consumption practices (Bidit et. al, 2020).

1.2. Collaborative learning

In relation to the formative and interactive process of university students within participatory collectivities that act through ICT, “ubiquitous learning” emerges (Burbules, 2013; Gros and Maina, 2016). From the blurring of borders between formal, non-formal and informal spheres sifted by mediated experiences, the consolidation of digital technologies as cognitive and affective prostheses and the emergence of citizen groups that promote other techno-social contracts, emerges the so-called “expanded education” (Díaz and Freire, 2012; Uribe-Zapata, 2018).

This connects with the so-called “digital natives” (Prensky, 2001, 2005) which refers to those generations that did not need classrooms to demonstrate an apparently innate mastery in the management of digital devices. At this point, digital literacy is understood as a combination of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and, above all, a social practice (Buckingham, 2002; Livingstone and Das, 2010). More recently in Spain, it has been shown how young people learn from and with their peers, through a series of interactions that occur in times of leisure and socialisation (Scolari, 2018).

Collective interaction through collaborative platforms such as Wuolah highlights the importance of collaborative learning pedagogy (Zhang, et al., 2021) focused on enriching the collective agency of students and co-constructing deep knowledge, rather than on the performance of regular learning tasks or verbal (writing and reading) expression and comprehension strategies (Pérez-Rodríguez, 2020).

1.3. Collective experiences in the teaching field

Based on social constructivism (Vygotsky, 1978), learning is considered a socially-situated process and is optimised when students actively and jointly construct their knowledge (Nie and Lau, 2010; Smith et al., 2004). In learning communities, university students share their knowledge by fostering a culture of participation, which can also contribute to improving academic performance (Brouwer et al., 2022). The strategy based on seeking help from peers is a self-regulation strategy that contributes to learning and academic performance (Ryan et al., 2001).

Collective online experiences applied to the teaching environment generate collective knowledge construction behaviours (De la Fuente Prieto et al., 2019). These processes of collective cognition rise above the shared objective of collective effort in the learning activities of multi-agent interaction. The pedagogical implications inspired by the collective cognition cycle are that teachers should guide students to engage in high-quality collective knowledge-building based on a group cognitive conflict, while developing students' perception of collective agency (Zhang, et al., 2021).

Nowadays, educators must think about how to teach both legacy and future content in the language of digital natives (Prensky, 2001). This is given the essential role they can play as developers of transmedia competencies, integrating them into the teaching-learning processes (Scolari, 2018; Alonso and Terol, 2020).

1.4. Prosumers and digital participatory culture

Content creators in the digital ecosystem no longer respond to a mathematical, two-way model (Shannon and Weaver, 1948), but rather to a continuous exchange in which “the roles of narrator and recipient are hybridised in co-creation, and in the figure of the prosumer” (Pérez-Rodríguez, 2020).

In these new consumers and creators of digital content, it is essential to emphasise the so-called culture of participation, that is, one in which digital and media use practices are associated with the concept of sharing, publishing, recommending, commenting and re-operating digital content, locating and establishing dispersed connections under a new set of rules. (Jenkins et al., 2015). That is, to apply the possibilities of informal learning to formal education, thus promoting a more empowered citizenship (Jenkins, et al., 2006).

Bruns (2008) refers to a type of participation, “pro-use,” based on technical possibilities that encourage an iterative approach to tasks, fluid roles and a lack of hierarchy, shared rather than owned material and granular approaches to problem-solving. To this must be added the emotional component that these collaborative networks create and enhance (Pérez-Rodríguez, 2020).

Through daily experiences on the network users share their ideas and concerns, which turns the culture of participation into a way of collaboration, transforming social networks ‘into an instrument of diffusion, promotion, modification of social behaviours, definition of identities, grouping and social movement, among other topics’ (Vizcaíno-Verdú et al., 2019, p. 217).

1.5. Objectives and hypothesis

This article carries out a case study of the collaborative platform Wuolah in order to analyse the role of this type of collaborative platform in the university teaching environment and its ability to develop collective experiences and promote a culture of participation. We understand that this phenomenon involves four fundamental actors that will form the pillars of this research: 1) the Wuolah platform; 2) the student creator of content (the one who shares his/her notes); 3) the student consumer and evaluator of that content (the one who downloads the notes of others); and 4) the faculty.

Thus, we set ourselves the following specific objectives:

-

To describe the collaborative platform Wuolah: know its history and current situation and define its operation and web structure.

-

To find out the perception and assessment of students and university faculty about this platform and its possibilities in the development of collective learning experiences in the university environment.

-

To analyse the representation of students who create content (prosumers), as well as that of students who consume it. In this sense, to detect the reliability that the digital community grants to shared content and evaluation mechanisms.

-

To glimpse the teaching possibilities of this collaborative platform and its possible contribution to the development of a participatory culture in the university learning-teaching process.

We start from the premise that with the arrival of ICT and the social web, new ways of teaching and learning are promoted thanks to the innumerable tools offered by Web 2.0. However, our first hypothesis (H1) suggests that there is a distant and very different assessment of the application of digital platforms such as Wuolah in the teaching field between teachers and students, with much reluctance on the part of the former and very good acceptance by the latter. The second hypothesis (H2) we are working with is that students have become active creators and generators of content that they share with the community, which values this work positively and, in general, trusts the work of its peers. Finally, the third hypothesis (H3) suggests that a good use of this tool, under the teacher’s guidance, can contribute to the development of collective university experiences capable of promoting collaborative learning.

2. Material and Methods

This research takes as a reference the basic premises previously put forward around collectivity and the incorporation of collaborative tools in the digital ecosystem and their application in the teaching-learning processes. For this purpose, we use an empirical-analytical methodology through a triangulation of different methods, both qualitative and quantitative.

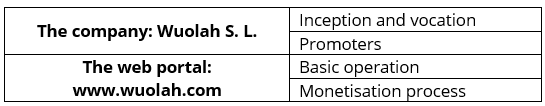

In the first place, we carry out a reading and bibliographic review on the concept of collectivity and on the application of ICT and digital platforms to the teaching field. Subsequently, a case study of the collaborative platform Wuolah is proposed, stemming from a descriptive analysis based on a series of variables related to the company (Wuolah S.L.) and others on the web portal in which they offer their services (http://www.wuolah.com).

Variables analysed in the descriptive study of Wuolah

Source: own elaboration

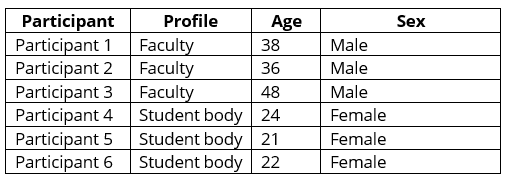

The next phase consisted of an exploratory qualitative study based on a series of semi-structured interviews using non-probability sampling by judgement for the selection of participants. Taking into account the universe of our object of study, three interviews have been carried out with current students of any of the degrees in Communication and another three interviews with current professors of any of the degrees in Communication, all of them from the University of Seville, during the months of September and October 2021. Aware of the importance of achieving active listening (García-Matilla, 2022) among the actors involved, these interviews have offered us rich and in-depth information, which has been fundamental not only as a first approach to the problem, but as a basis for the construction of the rest of the methods.

Data of the participants interviewed

Source: own elaboration

All the interviews follow a very similar structure and question scheme, adapted in the case of teachers or students, so that the answers provided by the participants can be compared and contrasted with each other.

Areas of interviews with teachers and students.

Source: own elaboration.

Next, and considering the methodological triangulation and the objectives set out, it was decided to include another quantitative method by conducting a survey, taking as a sampling frame the current university students of any Degree in Communication (Advertising and Public Relations, Audiovisual Communication, or Journalism) at the University of Seville or graduates who have graduated in the last five years, i.e. from the 2016/2017 academic year onwards. It is very common in academic literature to opt for university students as the population framework for carrying out these type of studies (Baelo and Canton, 2010; Cabero-Almenara and Marín-Díaz, 2014; Chawinga and Zinn, 2016; Espuny et al., 2011; Gewerc-Barujel et al., 2014; Gutiérrez-Castillo et al., 2017; Meso et al., 2011, p.137-155; Serra and Martorell, 2017).

The sample was selected using the non-probability sampling technique (Albert, 2006; Gil et al., 2008) by snowballing (Goodman, 1961), in such a way that the sample increases as the first participants invite their acquaintances to collaborate as well. For the calculation of the sample we take into account that the population from which we start is finite, as according to the Statistical Yearbooks of the University of Seville since the 2016/2017 academic year a total of 4 716 undergraduate students have studied and/or are studying at the Faculty of Communication. In this way, a confidence level of 95 % has been adopted and a margin of error of 5.7 % has been considered, so that 278 participants are sufficient for this first quantitative approach. In the configuration of the sample we find a predominance of the female gender, which represents 80.3 %, compared to the remaining 19.7 % of the male gender, and an average age of 21.36 years.

To meet the objectives set, an ad hoc questionnaire was constructed, consisting of three dimensions that are broken down into 26 items. After the bibliographic review of the object of study and the performance of the semi-structured interviews mentioned above, we propose these dimensions based on the proposals by Gutiérrez-Castillo et al. (2017) and by the Marco Común de Competencia Digital Docente (Common Framework of Digital Teaching Competence) of the National Institute of Educational Technologies and Teacher Training (2017), which read as follows:

Dimensions of the questionnaire

Source: own elaboration

For the validation of the survey we used two procedures. In the first place, we conducted an in-depth interview with a student to check the adequacy and correct understanding and interpretation of the selected questions, after which it was decided to simplify some sections of the questionnaire, as well as to change certain terms. The second step consisted of a panel of 6 experts who were provided with the questionnaire and a validation instrument that included 10 criteria (coherence, clarity, methodology, sufficiency, expertise, intentionality, organisation, relevance, coherence, and timeliness) that had to score from 1 to 4 accordingly (1. Strongly disagree, 2. Disagree, 3. Agree and 4. Strongly agree) and in which they could include observations. We obtained a total score of 189, and were able to identify the worst-rated aspects and implement improvements to our questionnaire thanks to expert feedback. Finally, the survey was conducted online through Google Forms during the month of December 2021.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive analysis of the Wuolah platform

Wuolah is a web platform developed by four students from the University of Seville (Javier Ruiz, Jaime Quintero, Francisco José Martínez and Enrique Ruiz) launched in 2016 where university students can share their notes for free and earn money with each download. It is one of the most used platforms by university students, “with 2.5 million registered students, 500 000 active users per month and more than 5 million documents uploaded” (Pereira, 2022).

The platform encourages the participation and collaboration of its users through weekly raffles. Wuolah is also present on the main social networks, with active profiles on Twitter (@Wuolah), Instagram (@Wuolah_apuntes) and Facebook (@Wuolah) with 27 356 followers, 13 200 followers and 7 423 followers respectively as of March 2022.

Wuolah presents itself as more than just a notes exchange platform. It aims to generate a real community in which users are the true participants in this learning experience. We find Top profiles, which are the best notes-uploading users, both in terms the amount of material published and the positive ratings and recommendations of other users. Moreover, these Top Wuolers can offer themselves as private teachers for the rest of the users, giving classes through the platform itself and charging for them at the rate that each one considers appropriate. In addition, the platform allows users to ask questions, answer other colleagues' questions or tell their community what they think can help other colleagues.

All this within the framework of a collective and collaborative space that, in the words of Pablo Pedrejón, of Seaya Ventures, a fund that has invested in Wuolah, “is reinventing secondary and university education like no other platform on the market. The passion generated by the current platform among students is only the starting point to continue developing products that transform learning” (Pedrejón cited in Pereira, 2022).

3.2. Interviews with teachers and students

In the interviews carried out, the perception of the influence of this type of platform applied to university education is questioned by the interviewed teachers, while for the students it is evident that this influence helps better teacher-student communication. There is unanimity that ICT can be useful in the classroom to improve the teaching experience and to achieve learning objectives by encouraging student involvement.

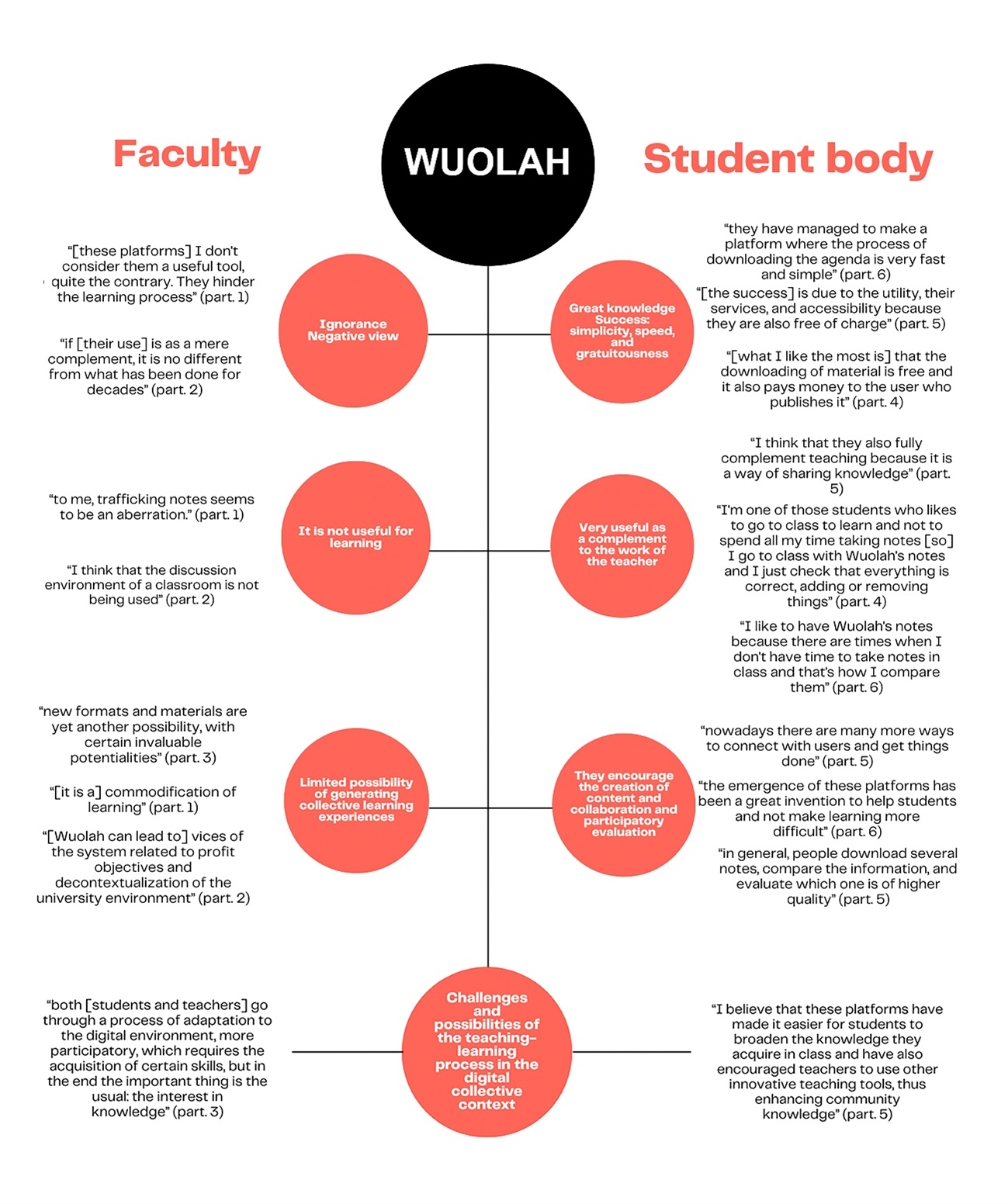

The analysis of the interviews has also allowed us to generate a series of categories (Figure 1) following first open coding and then axial coding. The first category refers to the general perception which is divided into the subcategories of knowledge/ignorance and negative view/positive view. The second category focuses on the usefulness of this platform for teaching and learning, with the subcategories of useful/useless and favourable/unfavourable. Thirdly, we identify a category based on the possibility of creating collective learning experiences, where collaboration and participation are included. Finally, a category is presented related to the challenges in the current teaching-learning process, together with the subcategories of adaptation and innovation.

Regarding the inclusion of collaborative online notes-sharing platforms such as Wuolah and its growing popularity among university students, the faculty confesses not knowing what the real keys to their success are. The three teachers interviewed were familiar with Wuolah to a greater or lesser extent, although none of them had ever used this or other similar platforms, and they perceive them as unfavourable for the success of teaching or, in the best of cases, not very relevant. The majority of the students state that Wuolah is one of the most-used tools throughout the course and stress that the keys to Wuolah's success are its simplicity, speed, free nature, variety of content, and the possibility of earning money.

The idea that the new digital media can develop collective learning experiences and a participatory culture in university teaching is held by a minority of teaching staff. The students, on the other hand, do believe that information technologies and spaces such as Wuolah encourage not only the creation of content by students, but also the evaluative capacity of the rest of the users who collaborate and participate in alternative learning environments.

All participants agree on the changes in the role of teachers and students in learning, based on greater involvement and participation of both, the acquisition of certain skills, the culture of participation and the generation of collective experiences inside and outside the classroom.

Figure 1

Results of teacher and student interviews

Source: own elaboration

3.3. Student survey results

The questionnaire consists of 26 items that are established in 3 dimensions, from the most general to the specific: digital skills and technological and information literacy of university students (dimension 1); the conception of collectivity and the culture of participation in the network and its potential for generating collaborative learning experiences (dimension 2); the creation of digital content, the role of university prosumers, and the perception and reliability for the rest of the community (dimension 3).

To know the internal consistency of the questionnaire, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient has been calculated for each dimension, obtaining 0.764 for dimension 1, 0.700 for dimension 2 and 0.804 for dimension 3; in all cases the values are above the minimum acceptable, so we can affirm that the scale has a valid construct (Cronbach, 1951).

The first question (item 1, dimension 1) reveals that the majority of respondents (85.2 %) consider that they have sufficient technical skills to surf the Internet successfully. In terms of their ability to identify relevant information on the Internet and check its validity (item 2, dimension 1), respondents consider themselves somewhat less skilled in this respect, with only 66 % believing that they can do this task with ease.

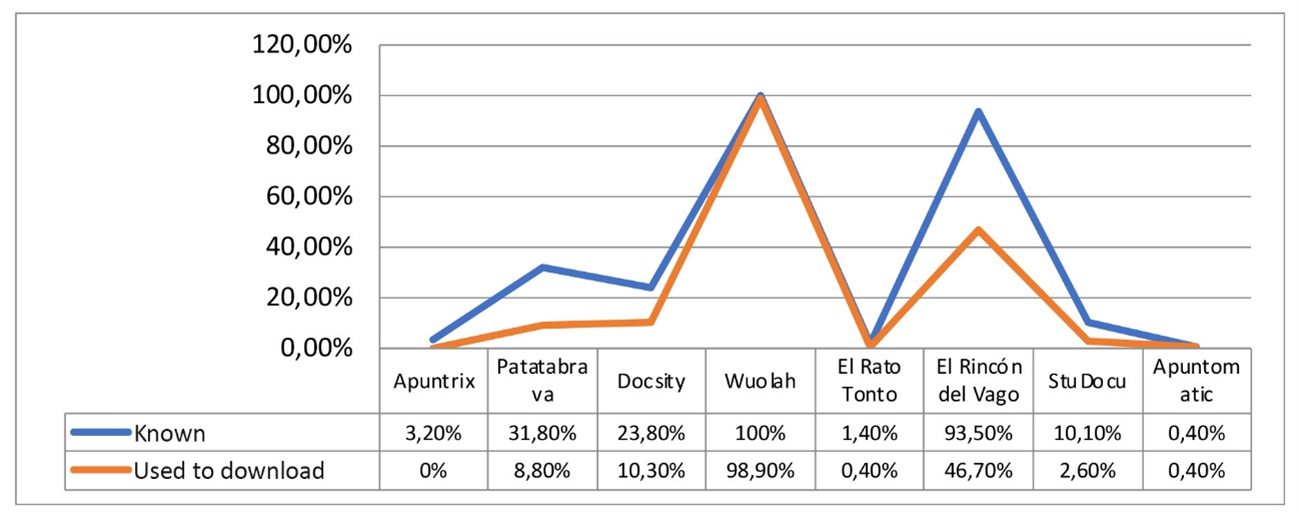

The most popular collaborative platform to share notes and teaching material among the surveyed students is Wuolah. It is also the most-used, as recognised by 98.9 % of respondents, followed by El Rincón del Vago and, at some distance, Patatabrava and Docsity.

Graph 1

Collaborative platforms that university students know and/or use (items 5 and 6 of the questionnaire, dimension 2)

Source: own elaboration

69.2 % of students perceive the possibility of becoming prosumers by creating original and own content through technologies and digital environments (item 4, dimension 3). However, it is less common for them to be the generators of these digital contents themselves, since only 31.77 % say they have published their notes on the web in order to share them with other colleagues.

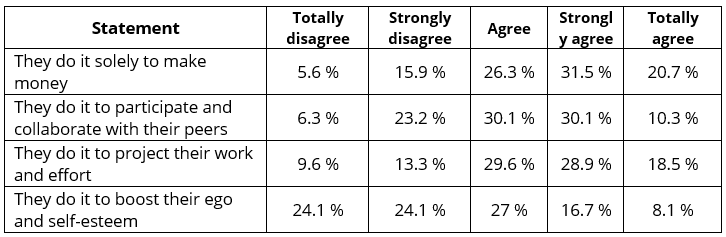

The opinion that university students have of those who do decide to develop and publish their notes on platforms such as Wuolah (items 8, 9, 10 and 11, dimension 3) is based on the idea that the main reason is economic along with the possibility of projecting their effort and work. In contrast to the previous widely-accepted statements, it is also widely accepted that these students share their notes to “participate and collaborate with their peers.”

Student perception of university prosumers who share their notes on Wuolah or other similar platforms (items 8, 9, 10 and 11, dimension 3)

Source: own elaboration

With respect to the above (Table 5), we have detected that there is a high negative linear correlation between the variable “making money” and that of “participating and collaborating with their peers;” that is, as students consider that prosumer students seek only to make money by uploading their notes to Wuolah, the view that they do so with a participatory and collaborative spirit helping their peers decreases, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of -0.621, a significant correlation at the 0.01 level. The same happens between the same variable of “making money” and that of “projecting their work and effort,” where a moderate negative linear correlation is also established with a Pearson coefficient of -0.443.

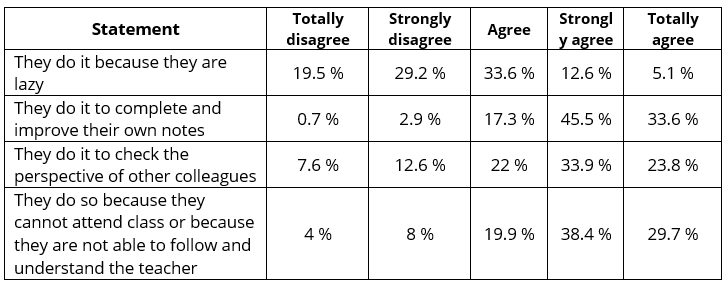

Table 6 shows the answers in relation to the culture of participation and the role of students who download notes through online platforms such as Wuolah (items 12, 13, 14 and 15, dimension 2). In general, a large percentage disagrees with the idea that students who use notes from the web are lazy. Moreover, many of them consider that they do it to check the perspective of other colleagues or because they cannot go to class or are not able to follow and understand the teacher.

Student perception of students who download notes on Wuolah or other similar platforms (items 12, 13, 14 and 15, dimension 2)

Source: own elaboration

A large majority of students, 90.6 %, show high confidence in prosumer students and the reliability of their content (notes and other didactic material) hosted on these digital portals (items 16, 17, 18 and 19, dimension 3). To determine the degree of reliability of the notes, students first look at the number of downloads and/or better ratings and, secondly, the popularity of their author.

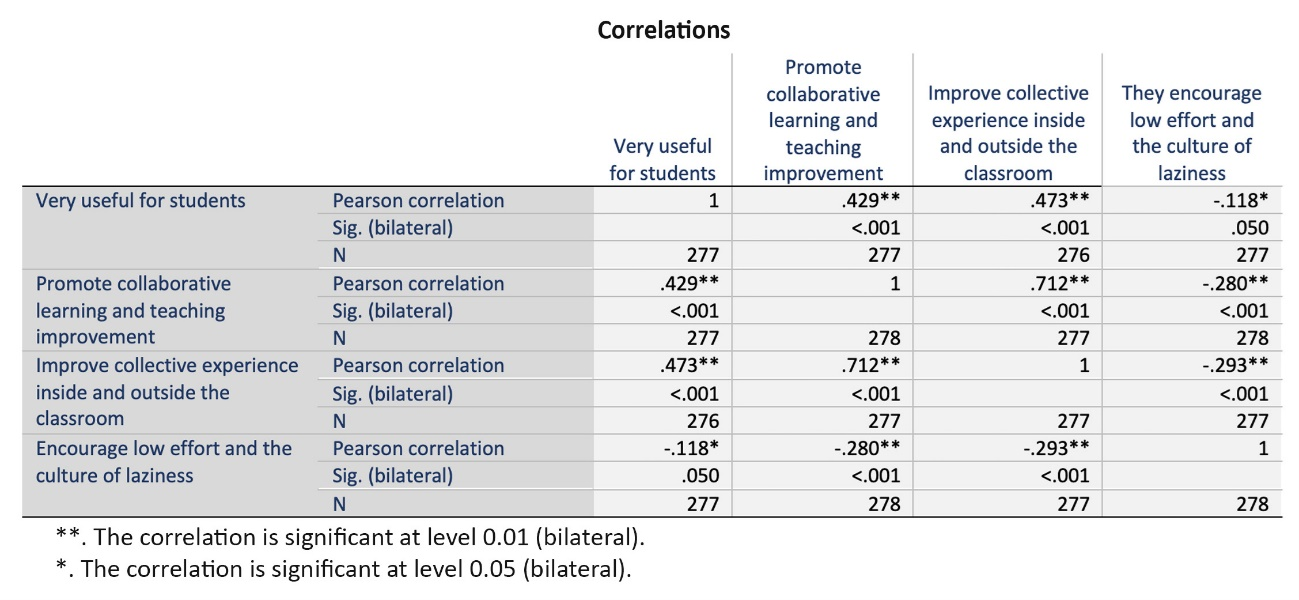

The students do perceive that Wuolah and other similar spaces contribute to building collective experiences in the teaching field based on collaborative learning (items 20, 21, 22 and 23, dimension 2): 94.9 % believe these platforms are very useful for the students; 73.3 % strongly or totally agree that these websites promote collaborative learning and teaching improvement; 70.6 % strongly agreed that they improve the collective experience inside and outside the classroom and the understanding of the subject.

However, these optimistic opinions contrast with a more negative view that believes these applications ‘encourage low effort and a culture of laziness’, an idea supported by 62.9 %. Logically, we find positive linear correlations between the first three variables, while these become negative with respect to the variable “low effort and culture of laziness” (table 7). This last variable maintains a moderate positive linear correlation with the one that interpreted the student consumer of notes as lazy (item 8, dimension 3), with a Pearson coefficient of 0.489 (significant at the 0.1 level).

Correlations between the descriptive variables on the perception and assessment of the students of Wuolah and other similar platforms (items 20, 21, 22 and 23, dimension 2)

Source: own elaboration

Question 24 (dimension 2) shows that 60.1 % consider that online platforms such as Wuolah encourage the culture of participation and collaborative learning of students. 65.7 % estimate that this type of application “promotes the discernment and evaluation capacity of the student to identify quality content with an analytical and evaluating attitude” (item 25, dimension 3). Finally, a large majority, 77.3 %, believe that the teachers' assessment of these platforms and their application to teaching is negative.

4. Discussion and conclusions

Taking into account the stated objectives and the data extracted from the descriptive analysis of the Wuolah platform, the interviews and the surveys in contrast to the theoretical review, the following conclusions can be drawn.

As for the first objective, to describe the collaborative platform Wuolah, we conclude that it is presented in the university scenario as a platform for quality notes, simple and quick to use, free for users and with the possibility of monetisation for content creators. It is a non-formal context for learning, combining real and digital environments and creating communities in which anyone can participate (De la Fuente Prieto et al., 2019).

We also confirm that it is the most popular and used collaborative platform among university students in Seville, as all respondents knew about it and nearly 99 % confirmed that they had downloaded notes from this application at some point.

The second objective of this research was to know the perception and assessment of students and university professors regarding this platform and its possibilities in the teaching field. In this regard, the existence of these collaborative platforms is estimated by almost all the students surveyed in a positive way due to their usefulness, promoting collaborative learning, and improving the experience inside and outside the classroom. This is consistent with the results obtained in similar previous studies, such as the case of the digital platform Entremedios (Marta-Lazo et al., 2022).

Teachers, on the other hand, observe these platforms with some reluctance and doubt with regard to their possible contribution in the teaching process. Students recognise this negative perception of teachers, based mainly on the fact that such platforms may encourage low student effort and the loss of a sense of shared time in the classroom. All this comes to reaffirm our first hypothesis (H1), according to which there is an opposite assessment between students and teachers about the usefulness of platforms such as Wuolah in the teaching-learning process.

It can also be seen that the most disparate aspect between the perception of students and teachers is related to the idea that platforms such as Wuolah promote the concept of collectivity and a culture of participation. Only one of the professors interviewed pointed out that the use of these tools can be well received, as long as it is a complement to other practices. In this regard, Wuolah highlights the importance of the collaborative learning pedagogy: teachers must guide students and promote their ability to develop active learning by integrating various sources of knowledge (Zhang, et al., 2021). In fact, both the interviews and the student surveys show that a large majority use Wuolah as a preliminary basis for the subject, complement and improve their own notes and check the perspective of other colleagues.

In relation to the third objective, to analyse the representation of students who create content (prosumers), as well as that of students who consume it, students are convinced of the possibilities of these platforms to improve student involvement and enhance their ability to create digital content, becoming university prosumers who are highly trusted by the rest of the community. However, the data also show that the role that students usually adopt with respect to this platform is that of content user rather than content generator, since less than 32 % claim to have published their own notes on the web in order to share them. This ties in with the theory of participatory inequality which holds that, in most online communities, 90 % of users are readers or observers of content but never contribute to the generation of content, 9 % of users contribute a little, and 1 % of users participate regularly (Nielsen, 2006). In this way, the second hypothesis (H2) would be partially validated, since this prosumer role of the student is confirmed, although it is also not found to be in the majority, since more than two thirds of the Wuolah users consulted adopt an observer and consumer role.

The last and fourth objective is answered in the results, which show the teaching possibilities of Wuolah and its ability to conceive educational strategies based on a digital culture of participation, the generation of content by students, and collaborative teaching. In fact, Wuolah is perceived as an opportunity to enhance collaborative work where the concept of sharing, publishing, recommending, commenting, and re-operating digital content is extended (Jenkins et al., 2015; Vizcaíno- Verdú et al., 2019). In this way, it is on a par with other collaborative platforms applied to the university environment, such as storytelling and transmedia narratives (Ossorio-Vega, 2014; Saavedra-Bautista et al., 2017).

Thus, we can partially corroborate the third hypothesis (H3) of this work, although we find aspects that do not allow us to claim full confirmation. Indeed, Wuolah reaffirms that these collaborative methodologies have not had an impact on university classrooms (Rodrigo-Cano et al., 2019), i.e. there has not been a true integration of this in the teaching dynamics of the teaching staff, although its use by the students is very widespread. All this despite the interest of both in incorporating digital and technological tools into the teaching dynamics. The real challenge is to take advantage of the digital space to facilitate teaching by integrating these practices into the teaching-learning processes (Alonso and Terol, 2020) within the framework of collaborative teaching capable of stimulating the involvement and participation of students and generating collective learning experiences.

That is why we see not only the opportunity but also the need to study how the Wuolah platform can contribute to collaborative teaching in the university environment. However, some limitations should be noted in this research. The first and most relevant is the difficulty in locating a sample of teachers who know this platform in depth, which would have enriched the results of the interviews. To this is added the scarcity of previous scientific studies regarding this particular platform, there being various works on Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, and other tools but none that specifically address Wuolah. Finally, and with a view to future lines of research, it would be appropriate to include as part of the sample other populations, i.e., teaching staff and students from other faculties and universities, in order to deepen comparative studies and broaden the vision of the phenomenon.

Author contribution

Noelia García-Estévez: Conceptualisation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualisation, Writing - original draft and Writing - revision and editing. Lucia Ballesteros-Aguayo: Conceptualisation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing - original draft and Writing - revision and editing. All authors have read and agree with the published version of the manuscript. Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

The work has been funded by the Department of Journalism of the University of Málaga.

References

Albert, María José (2006). La investigación educativa. Claves teóricas. Mc-Graw-Hill.

Alonso López, Nadia and Terol Bolinches, Raúl (2020). Alfabetización transmedia y redes sociales: Instagram como herramienta docente en el aula universitaria. Revista ICONO 14. Revista Científica De Comunicación Y Tecnologías Emergentes, 18(2), 138-161. https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v18i2.1518

Baelo, Roberto and Cantón, Isabel (2010). Las TIC en las Universidades de Castilla y León. Comunicar, 35, 59-166. https://doi.org/10.3916/C35-2010-03-09

Bidit L. Dey, Dorothy Yen and Lalnunpuia Samuel (2020). Digital consumer culture and digital acculturation. International Journal of Information Management, 51, 102057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.102057

Brouwer, Jasperina, De Matos Fernandes, Carlos A., Steglich, Christian E. G., Jansen, Ellen P.W.A., Hofman, W. H. Adriaan y Flache, Andreas (2022). The development of peer networks and academic performance in learning communities in higher education. Learning and Instruction, 80 [101603]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2022.101603

Bruns, Axel (2008). Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and Beyond: From Production to Produsage. Peter Lang.

Buckingham, David (2002). Crecer en la era de los medios electrónicos: Tras la muerte de la infancia. Morata-Paideia.

Burbules, Nicholas C. (2013). Los significados de ‘aprendizaje ubicuo’. Revista de Política Educativa, 4, 11-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v22.1880. A

Cabero-Almenara, Julio and Marín-Díaz, Verónica (2014). Posibilidades educativas de las redes sociales y el trabajo en grupo. Percepciones de los alumnos universitarios. Comunicar, 42, 165-172. https://doi.org/10.3916/C42-2014-16

Chawinga, Winner D. and Zinn, Sandy (2016). Use of Web 2.0 by students in the Faculty of Information Science and Communications at Mzuzu University, Malawi. South African Journal of Information Management, 18 (1), a694. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajim.v18i1.694

De la Fuente Prieto, Julián, Lacasa Díaz, Pilar and Martínez-Borda, Rut (2019). Adolescentes, redes sociales y universos transmedia: la alfabetización mediática en contextos participativos. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 74, 172-196. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2019-1326

Díaz, Rubén and Freire, Juan (2012). Educación expandida. Barcelona: Zemos98.

Espuny Vidal, Cinta, González Martínez, Juan, Lleixà Fortuño, Mar and Gisbert Cervera, Mercè (2011). Actitudes y expectativas del uso educativo de las redes sociales en los alumnos universitarios. Revista de Universidad y Sociedad del Conocimiento, 8 (1), 171-185. http://dx.doi.org/10.7238/rusc.v8i1.839

García-Matilla, Agustín (2022). Pantallas y dispositivos móviles. Una necesaria educación para la comunicación de la infancia. Revista ICONO 14. Revista Científica De Comunicación Y Tecnologías Emergentes, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v20i1.1807

Gewerc-Barujel, Adriana, Montero-Mesa, Lourdes and Lama-Penín, Manuel (2014). Colaboración y redes sociales en la enseñanza universitaria. Comunicar, 42, 55-63. https://doi.org/10.3916/C42-2014-05

Gil Flores, Javier, Rodríguez Gómez, Gregorio and García Jiménez, Eduardo (2008). Estadística básica aplicada a las ciencias de la educación. Kronos.

Goodman, Leo A. (1961). Snowball Sampling. Annals of Mathematical Statistic, 32,148-70. https://doi.org/10.1214/aoms/1177705148.

Gutiérrez-Castillo, Juan Jesús, Cabero-Almenara, Julio and Estrada-Vidal, Ligia Isabel (2017). Diseño y validación de un instrumento de evaluación de la competencia digital del estudiante universitario. Revistas Espacios, 8(10). https://acortar.link/Cm7Oe1

Instituto Nacional de Tecnologías Educativas y de Formación del Profesorado (2017). Marco Común de Competencia Digital Docente. Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport of the Government of Spain.

Gros, Begoña and Maina, Marcelo (2016). The future of ubiquitous learning. Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Hassan, Robert (2020). The condition of digitality: A post-modern Marxism for the practice of digital life. University of Westminster Press.

Jenkins, Henry, Ford, Sam and Green, Joshua (2015). Cultura Transmedia: La creación de contenido y valor en una cultura en red. Gedisa.

Jenkins Henry, Purushotma, Ravi, Weigel, Margaret, Clinton, Katie and Robison, Alice J. (2006). Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century, Chicago: The John D. and Catherine McArthur Foundation.

Leistert, Oliver (2017). Mobile phone signals and protest crowds: Performing an unstable post-media constellation. In Martina Leeker, Imanuel Schipper y Timon Beyes (Eds.), Performing the digital (pp. 137–154). Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/2129.

Livingstone, Sonia and Das, Ranjana (2010). Changing Media, Changing families: Polis Media and Family Series. LSE: Polis. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/30156/

Marta-Lazo, Carmen, Gabelas-Barroso, José Antonio, Nogales-Bocio, Antonia and Badillo-Mendoza, Miguel Ezequiel (2022). Aprendizaje Multimedia y Transferencia de Conocimiento en una Plataforma Digital. Estudio de Caso de Entremedios. RIED. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 25(1), 101-120. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.25.1.30846

Meso Ayerdi, Koldo, Pérez Dasilva, Jesús Ángel and Mendiguren Galdospin, Terese (2011). La implementación de las redes sociales en la enseñanza superior universitaria. Tejuelo, 12(1), 137-155.

Nie, Youyan y Lau, Shun (2010). Differential relations of constructivist and didactic instruction to students’ cognition, motivation, and achievement. Learning and Instruction, 20(5), 411-423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.04.002

Nielsen, Jakob (2006). The 90-9-1 Rule for Participation Inequality in Social Media and Online Communities. Nielsen Norman Group. https://acortar.link/zzYeOO

Ossorio-Vega, Miguel Ángel (2014). Application of Transmedia Storytelling in Spanish Universities: Collaborative Learning, Multi platform and Multi format. Internacional Technology, Science and Society Review, 3(2), 25-38. https://doi.org/10.37467/gka-revtechno.v3.1186

Pereira, María Jesús (24 February 2022). El fondo Seaya, la gestora Alter Capital y Proeduca entran en la plataforma de apuntes Wuolah. ABC Sevilla. https://n9.cl/oz49v

Pérez-Rodríguez, Amor (2020). Homo sapiens, homo videns, homo fabulators. La competencia mediática en los relatos del universo transmedia. Revista ICONO 14. Revista Científica De Comunicación Y Tecnologías Emergentes, 18(2), 16-34. https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v18i2.1523

Prensky, Marc (2001). Digital Natives. Digital Immigrants Part I. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424816

Prensky, Marc (2005). Teaching digital natives: partnering for real learning. Corwin press. https://acortar.link/NlGEbU.

Raymond, L.M. Lee. (2021). Collectivity, connectivity and control: reframing mass society in the digital era. International Review of Sociology, 31(1), 204-221. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2021.1913546

Rodrigo-Cano, Daniel, Aguaded Gómez, Ignacio and García Moro, Francisco José (2019). Collaborative Learning in Web 2.0: The educational challenge in high school. REDU. Revista de Docencia Universitaria, 17(1), 229-244. https://doi.org/10.4995/redu.2019.10829

Ryan, Allison M., Pintrich, Paul R. and Midgley, Carol (2001). Avoiding seeking help in the classroom: Who and why? Educational Psychology Review, 13(2), 93-114. https://acortar.link/536EsB

Saavedra-Bautista, Claudia, Cuervo-Gómez, William, and Mejía-Ortega, Iván Darío (2017). Producción de contenidos transmedia, una estrategia innovadora. Revista Científica, 28(1), 6–16. https://doi.org/10.14483/issn.2344-8350

Scolari, Carlos Alberto (2018). Adolescentes, medios de comunicación y culturas colaborativas. Aprovechando las competencias transmedia de los jóvenes en el aula. TRANSLITERACY H2020 Research and Innovation Actions.

Serra Folch, Carolina and Martorell Castellano, Cristina (2017). Los medios sociales como herramientas de acceso a la información en la enseñanza universitaria. Digital Education Review, 32, 118-129.

Shannon, Claude Elwood and Weaver, Warren (1948). The Mathematical Theory of Communication. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

Smith, Barbara Leigh, MacGregor, Jean, Matthews, Roberta and Gabelnick, Faith (2004). Learning communities: Reforming undergraduate education. Jossey-Bass.

Uribe-Zapata, Alejandro (2018). Concepto y prácticas de educación expandida: una revisión de la literatura académica. El Ágora USB, 18(1), 277-292. https://doi.org/10.21500/16578031.3456

Uribe-Zapata, Alejandro (2019). Cultura digital, juventud y prácticas ciudadanas emergentes en Medellín, Colombia. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 17(2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.11600/1692715x.17218

Vizcaíno-Verdú, Arantxa, De Casas-Moreno, Patricia and Aguaded Gómez, Ignacio (2019). Youtubers e instagrammers. Una revisión sistemática cuantitativa. En Ignacio Aguaded Gómez, Arantxa Vizcaíno-Verdú and Yamile Sandoval-Romero (Eds.), Competencia mediática y digital: Del acceso al empoderamiento (pp. 211-220). Grupo Comunicar Ediciones.

Vygotsky, Lev Semiónovich (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Zhang, Si, Chen, Hongxian, Wen, Yun, Deng, Lu, Cai, Zhihui and Sun, Mengyu (2021). Exploring the influence of interactive network and collective knowledge construction mode on students’ perceived collective agency. Computers & Education, 171, 104240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104240

Author notes

* Professor in Advertising and Public Relations. Department of Audiovisual Communication and Advertising. Faculty of Communication. University of Seville (US), Spain.

** Professor in the Department of Journalism. University of Málaga (UMA), Spain.

Additional information

Translation to English

:

M21Global

To cite this article

:

García-Estévez, Noelia, & Ballesteros-Aguayo, Lucia. (2022). The Use of Wuolah as a Collective Tool in the University Environment: Collaborative Teaching and Culture of Participation. ICONO 14. Scientific Journal of Communication and Emerging Technologies, 20(2). https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v20i2.1888

ISSN: 1697-8293

Vol. 20

Num. 2

Año. 2022

The Use of Wuolah as a Collective Tool in the University Environment: Collaborative Teaching and Culture of Participation

Noelia García-Estévez 1, Lucia Ballesteros-Aguayo 2